Marja's Hearts and Minds

As General David Petraeus assumes direct control of the war in Afghanistan, he and his officers—not to mention the policymakers back home—are pinning their hopes on improved cooperation with friendly locals. Traveling to the southern Afghan city of Marja, site of a major offensive this past February, photographer Micah Garen surveys the diverse cast of characters—soldiers, elders, farmers, even robots—whose actions will decide the mission’s outcome.

Micah Garen was in Marja in May, 2010, photographing with a 4×5 Wisner field camera, and the photo essay was published on Vanity Fair on July 26, 2010.

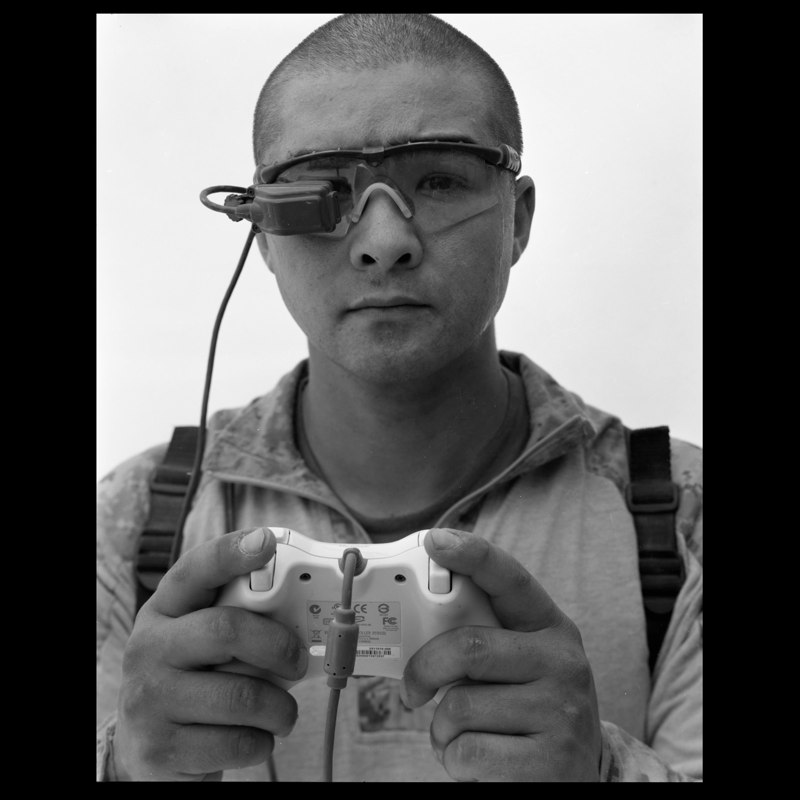

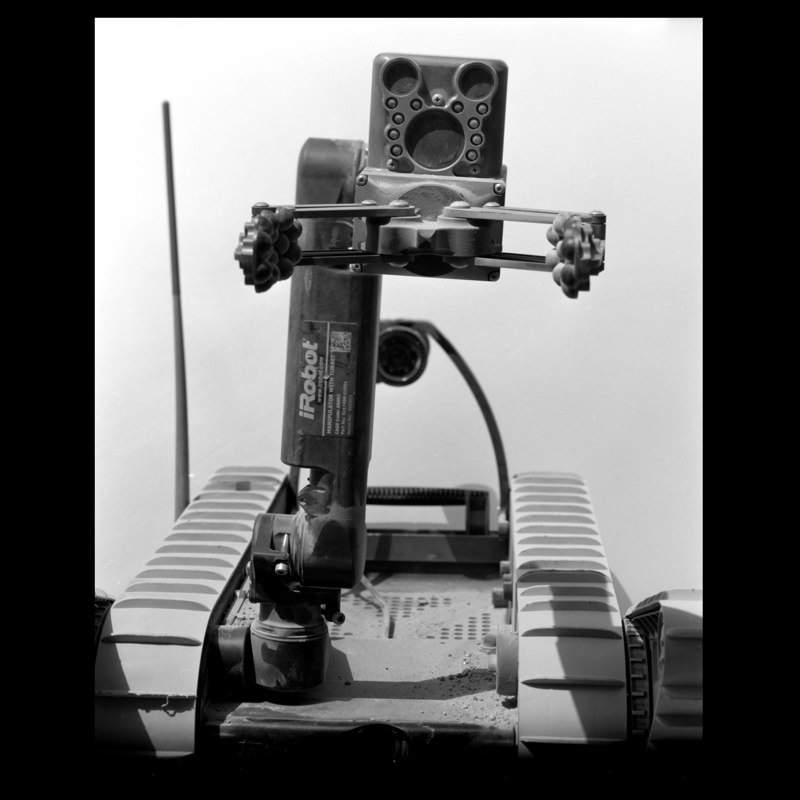

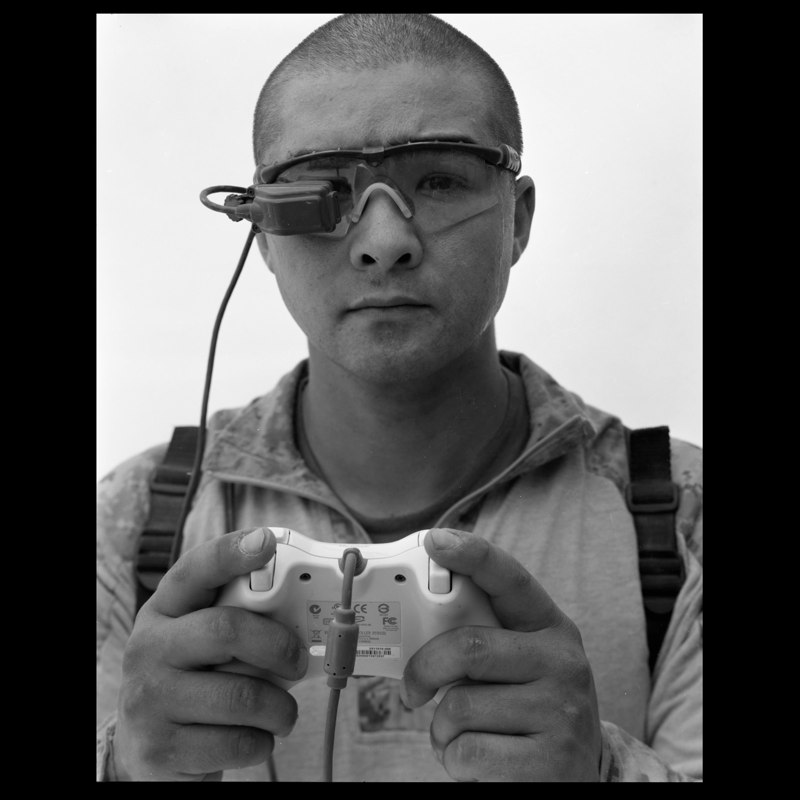

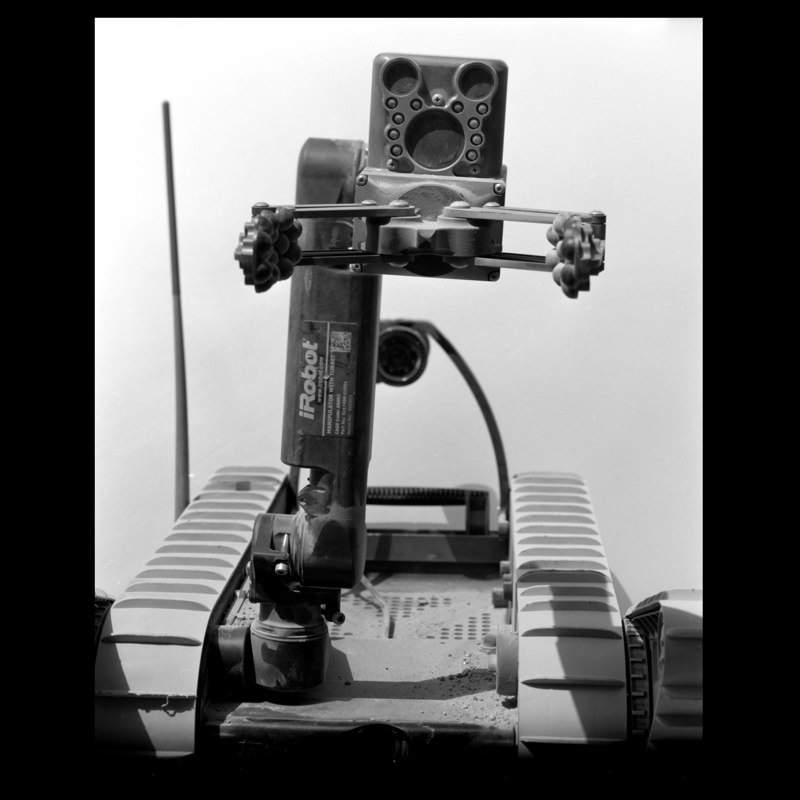

Sergeant Steve Dunning, from Milpitas, California, holds an Xbox controller and wears a pair of Oakleys fitted with a video display that controls the PackBot 310 SUGV bomb-disposal robot, a system that allows Marines to deal with I.E.D.’s remotely.

Haji Abdul Zahir was appointed the district chief of Marja in February during Operation Moshtarak. On July 12, he lost his job, with no reason given for his sudden departure. Before taking over the restive region, Zahir lived in Germany for 15 years, four of which he spent in prison for assaulting his stepson.

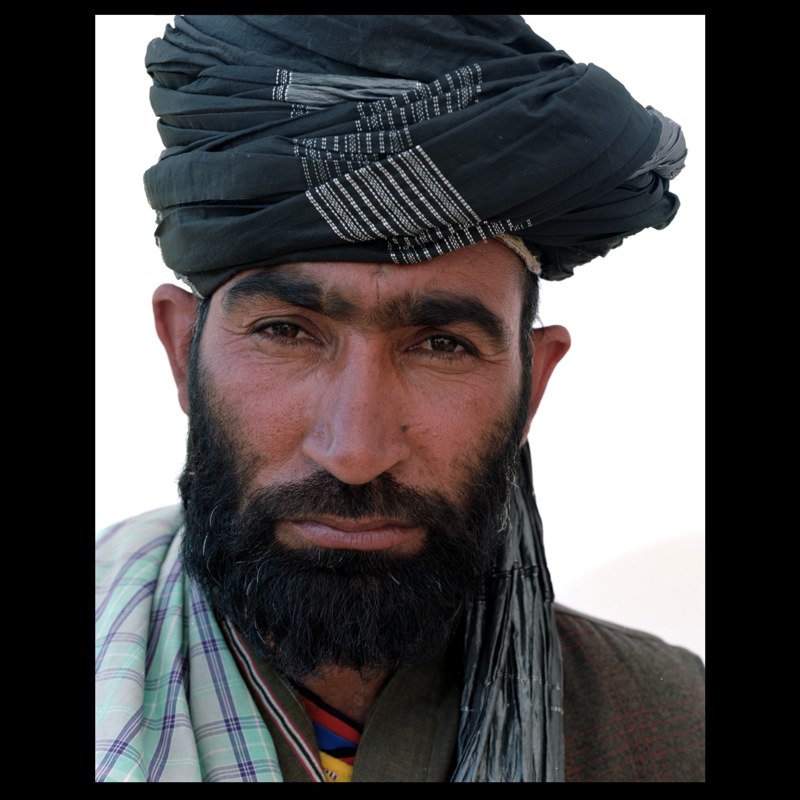

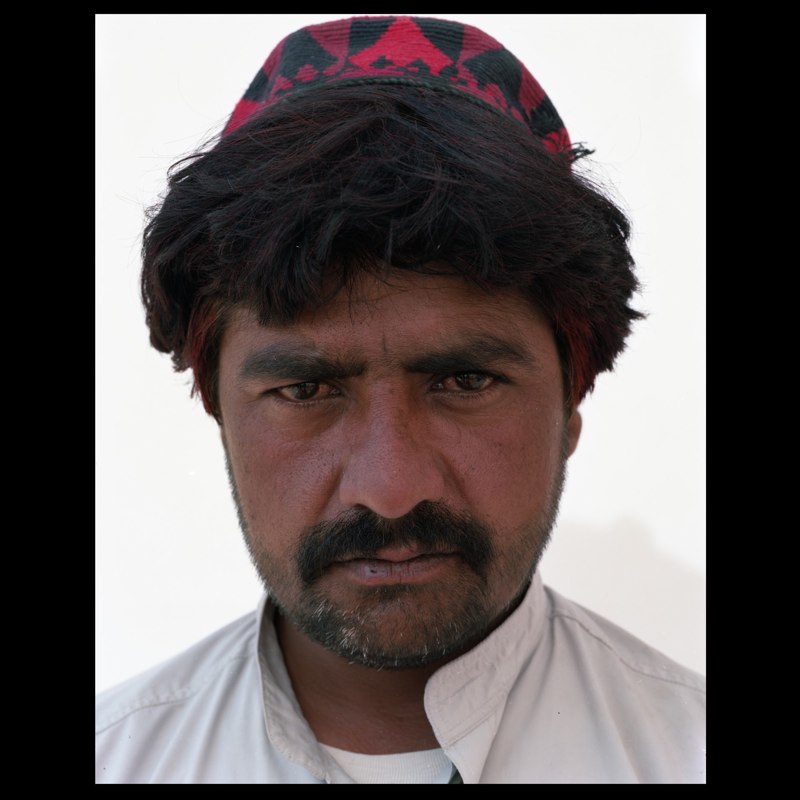

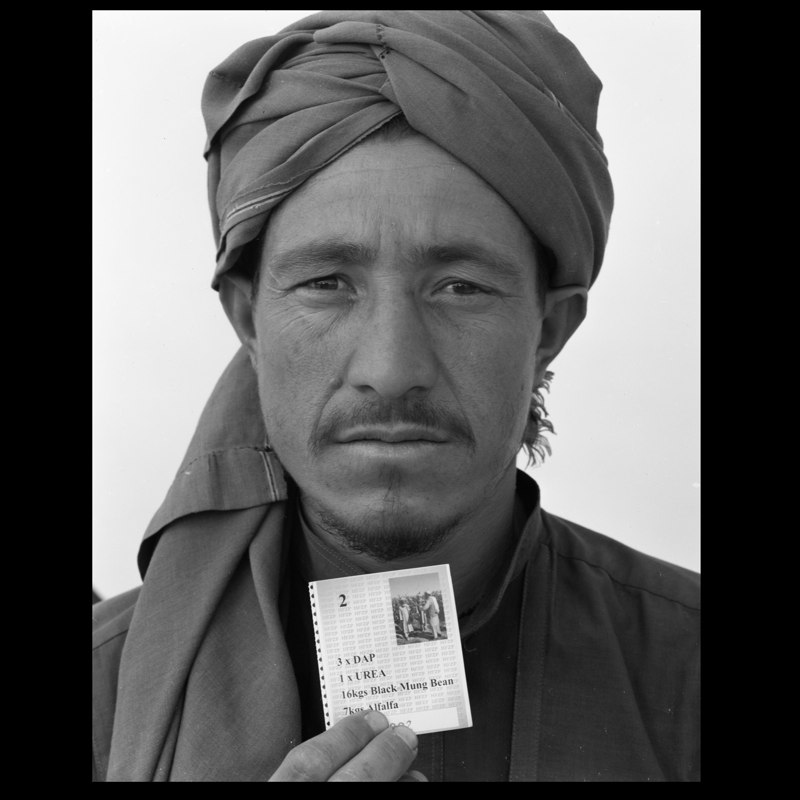

A farmer in Marja signing up for a Cash for Work program.

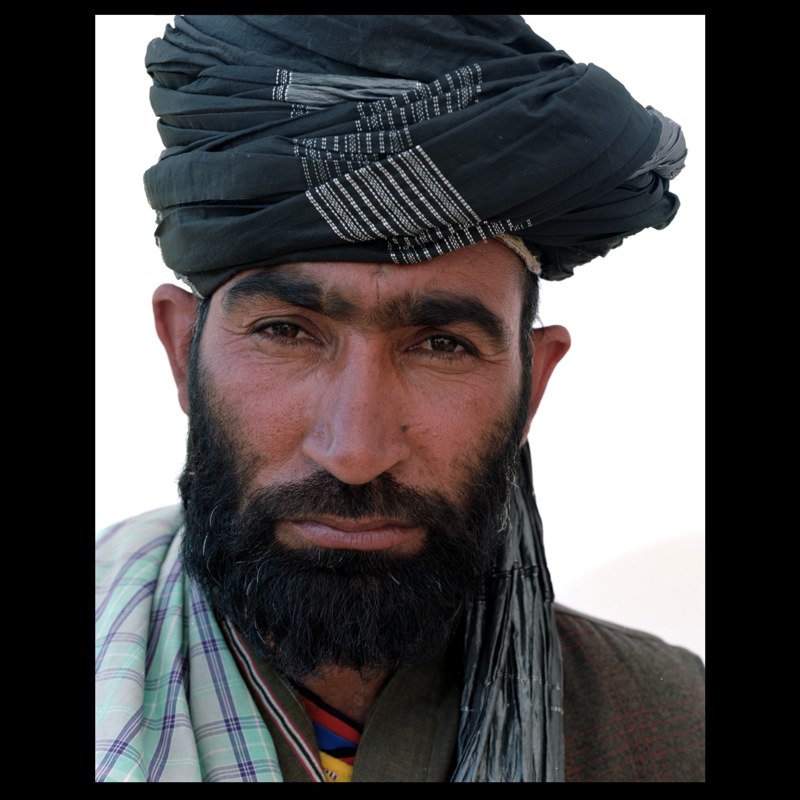

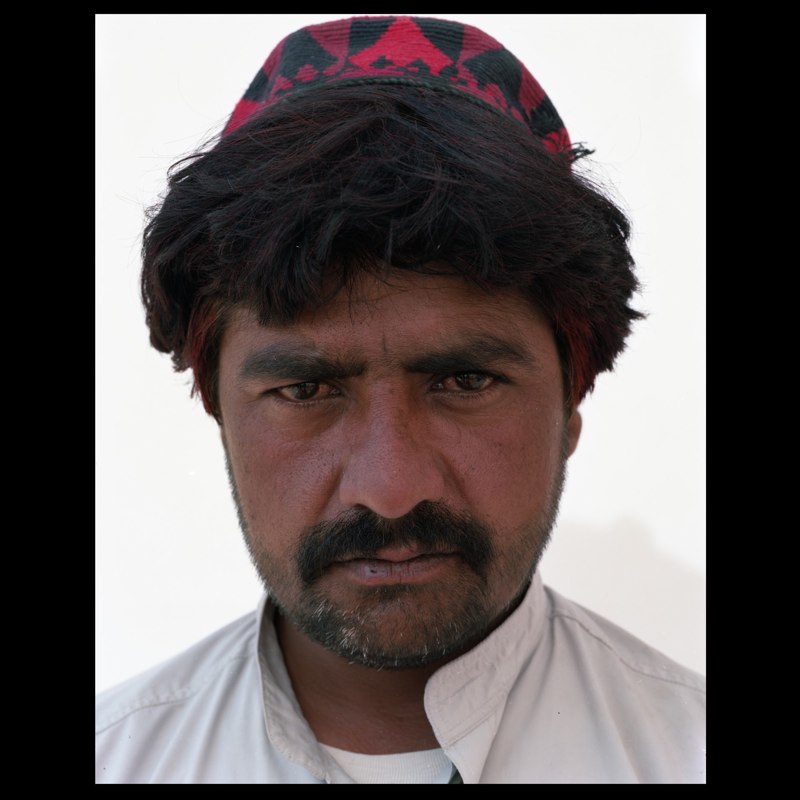

An Afghan villager waiting to sign up for the USAID Cash for Work Program.

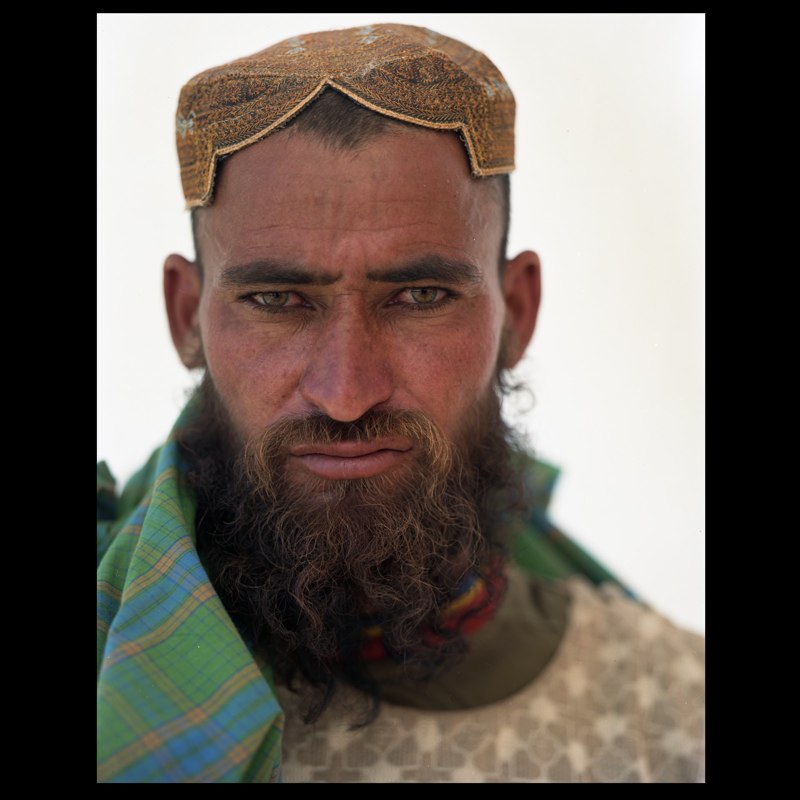

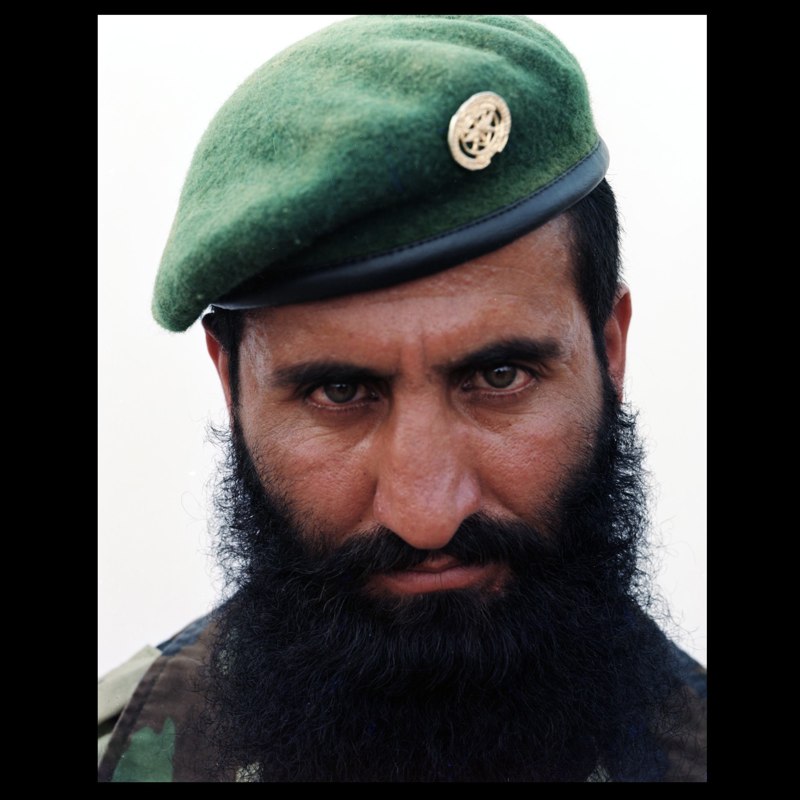

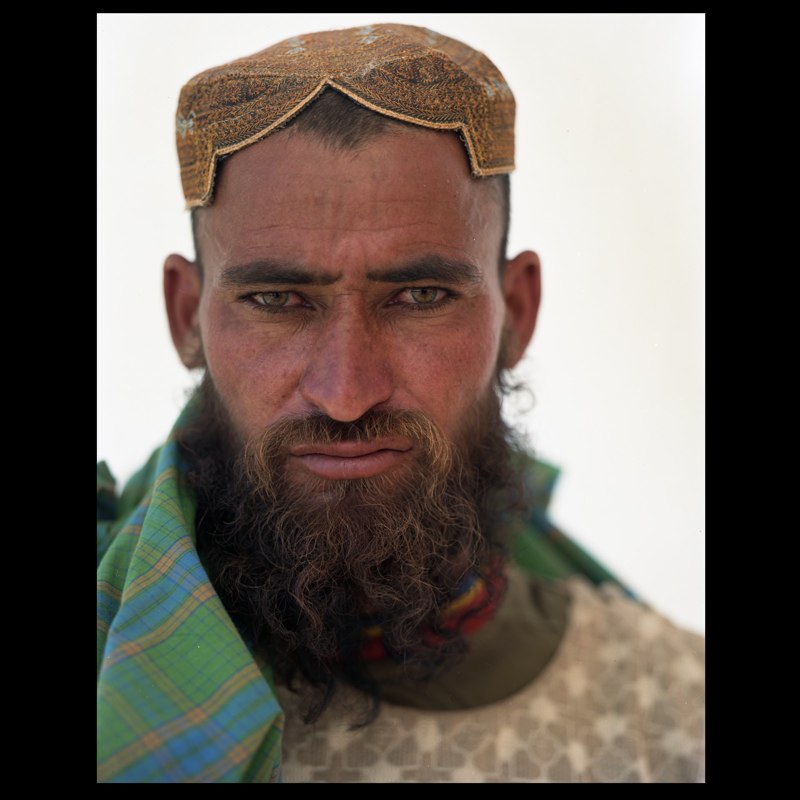

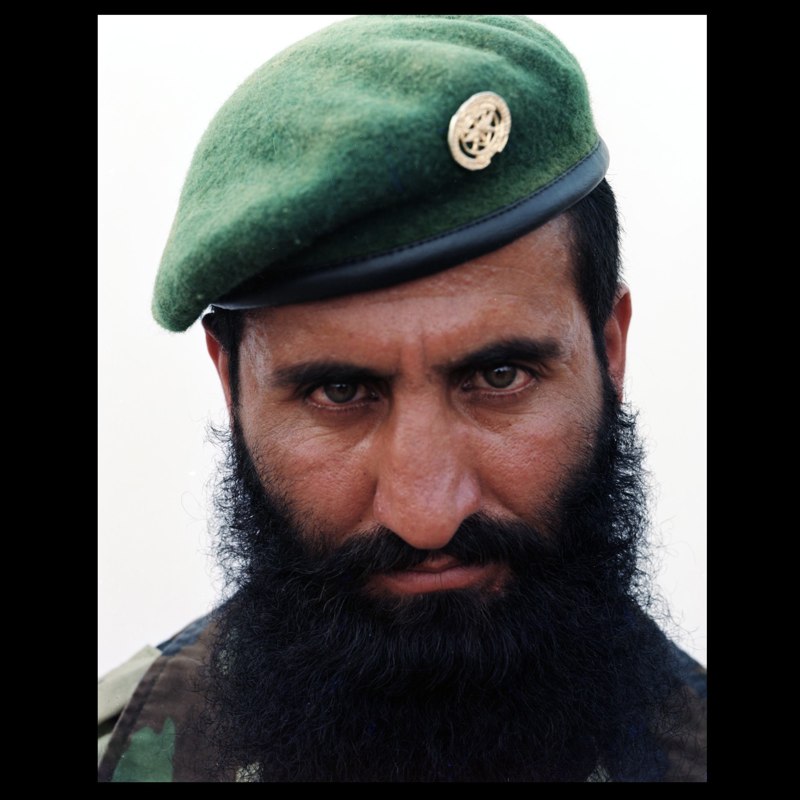

An Afghan National Army soldier in Marja.

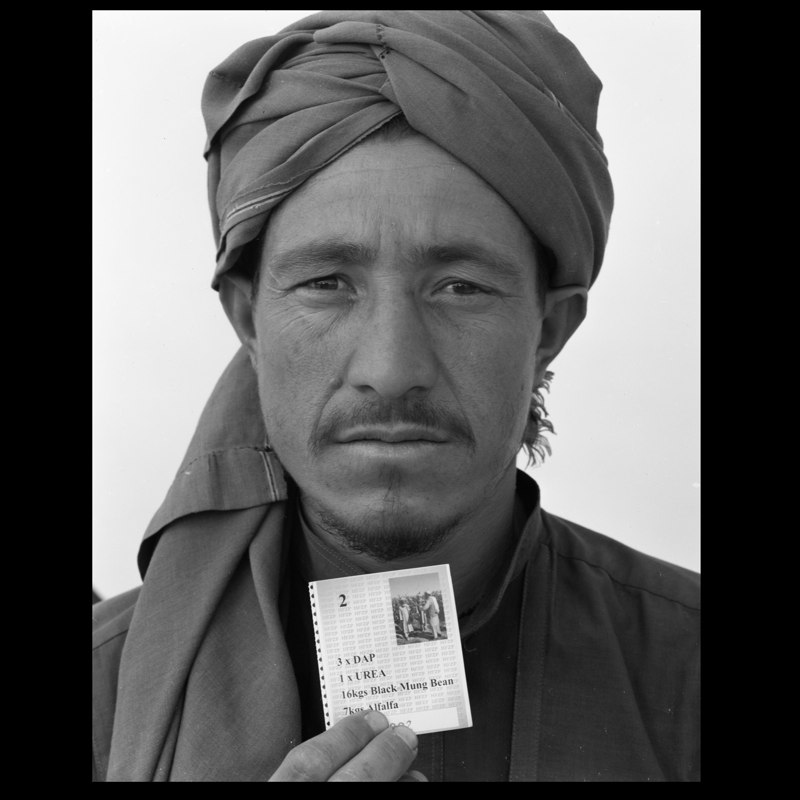

A poppy farmer in Marja who came to the government center to sign up for a USAID Cash for Work program that gives military-age men licit employment opportunities. Afghanistan supplies 90 percent of the world’s opium, according to a report by the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime.

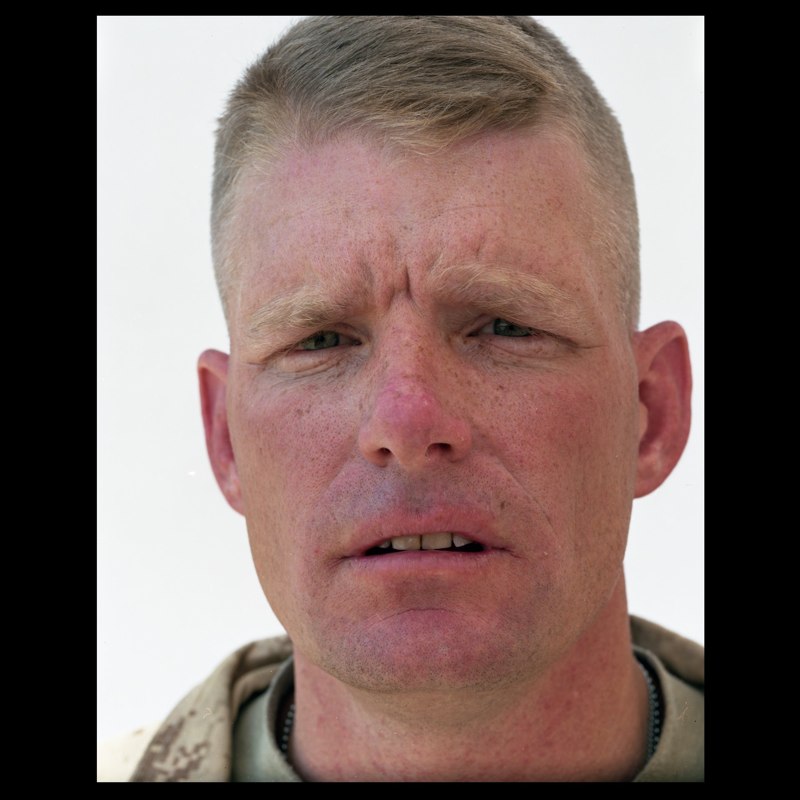

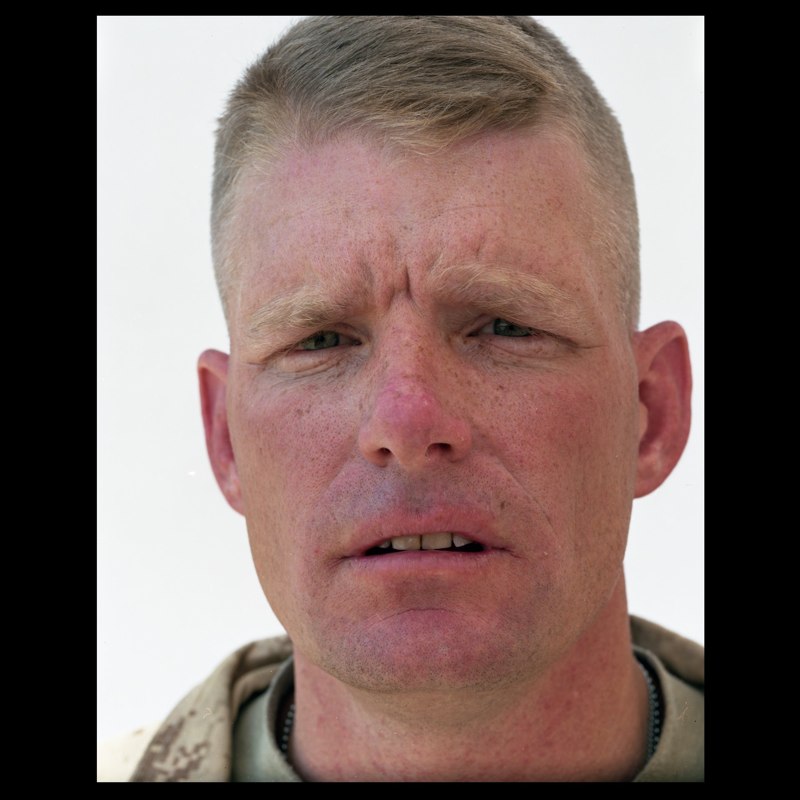

Colonel Brian Christmas, a Marine commander who took northern Marja as part of the International Security Assistance Force’s Operation Moshtarak in March. He was called up as part of President Barack Obama’s surge last fall. “This is a battle that has to have patience,” Colonel Christmas told me. “A rush to failure is the biggest risk.”

An Afghan National Army soldier in Marja.

Afghan linguist working for US Marine Civilian Affairs unit doing a retinal scan of a Marja villager who has come to pick up bags of wheat. The villagers are given a retinal scan, photographed and their fingerprints are entered into a national database used to identify criminals.

A villager in Marja waiting to sign up for the USAID Cash for Work program.

One of the bomb-sniffing dogs in Marja. The dogs—which have a mixed record and a high mortality rate—are trained to lie down in the road when they smell chemicals associated with improvised explosive devices (I.E.D.’s). They frequently suffer PTSD after a year or two of service.

A child in Marja.

A poppy farmer in Marja collecting seeds to grow other crops. Farmers are encouraged to convert poppy fields for use with other plants through various government programs in Marja.

A Marine Female Engagement Team (F.E.T.) member in Marja. F.E.T. units—first introduced in Afghanistan in February 2008—are made up of female Marines and soldiers with various specialties who conduct liaison work with Afghan women, often accompanying all-male foot patrols in remote villages. The most common question from Afghan women to female soldiers and Marines in Marja, according to one female Marine I spoke to, has been: “Do you have children?”

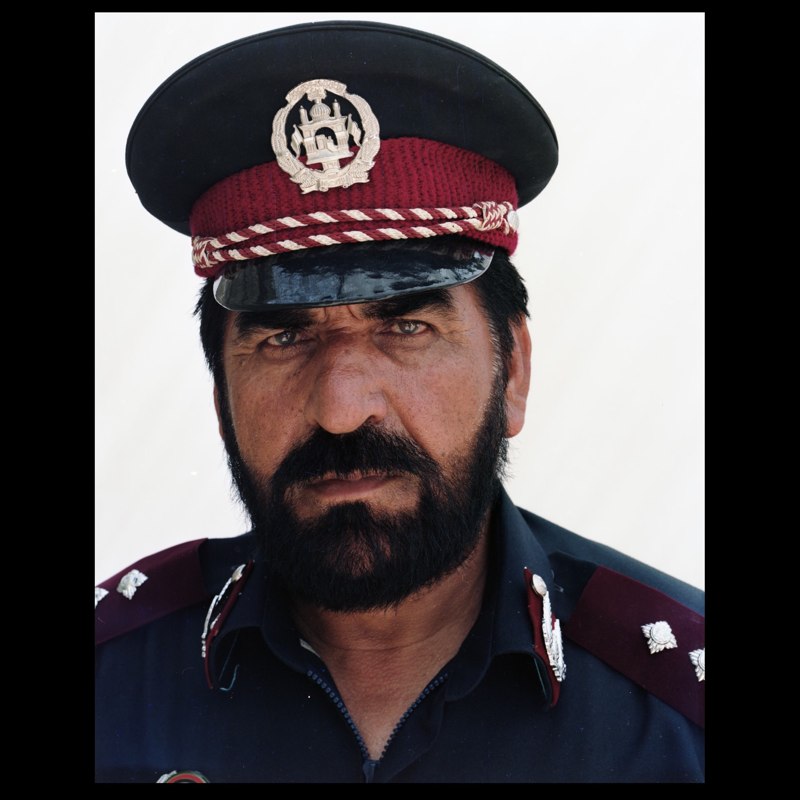

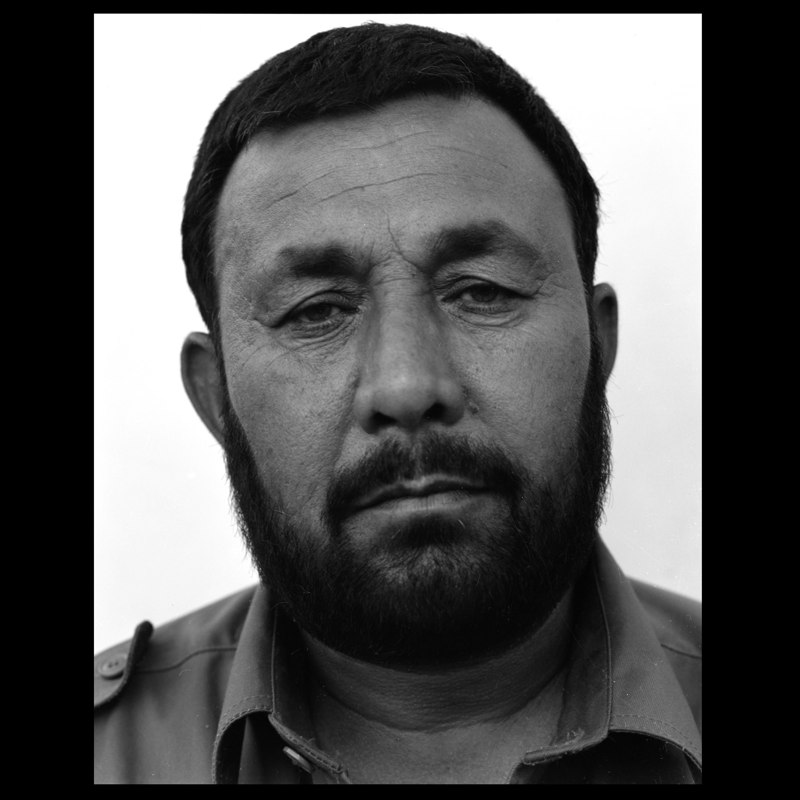

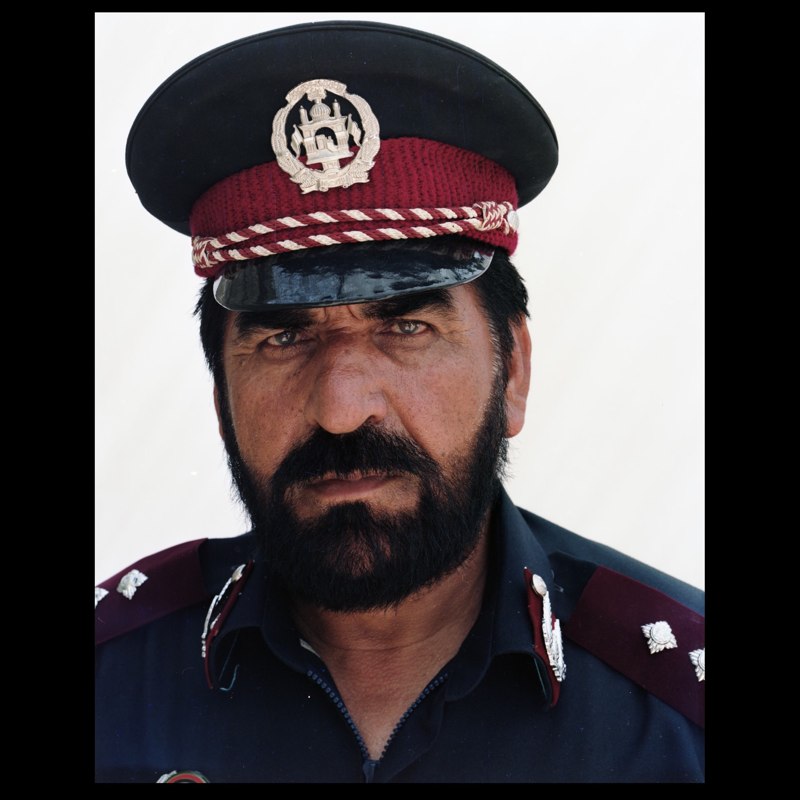

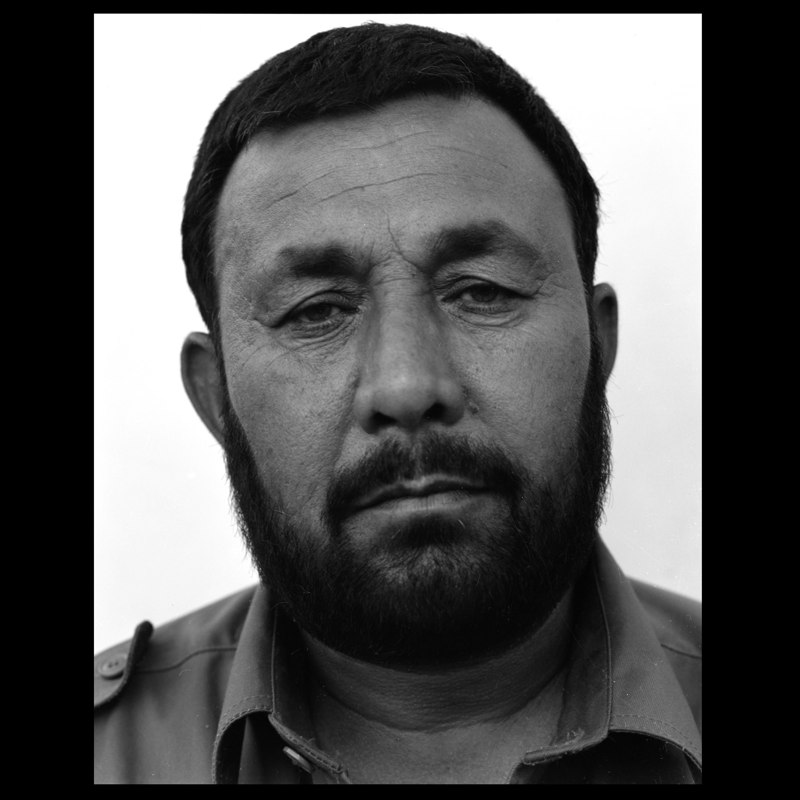

An Afghan National Civil Order Police commander in Marja.

The PackBot 310 SUGV bomb-disposal robot.

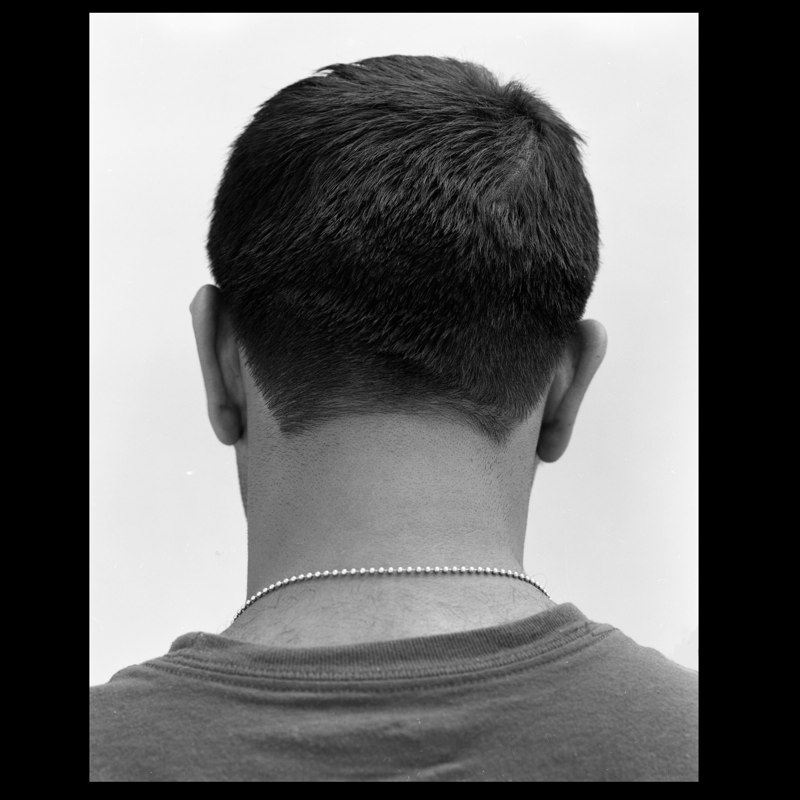

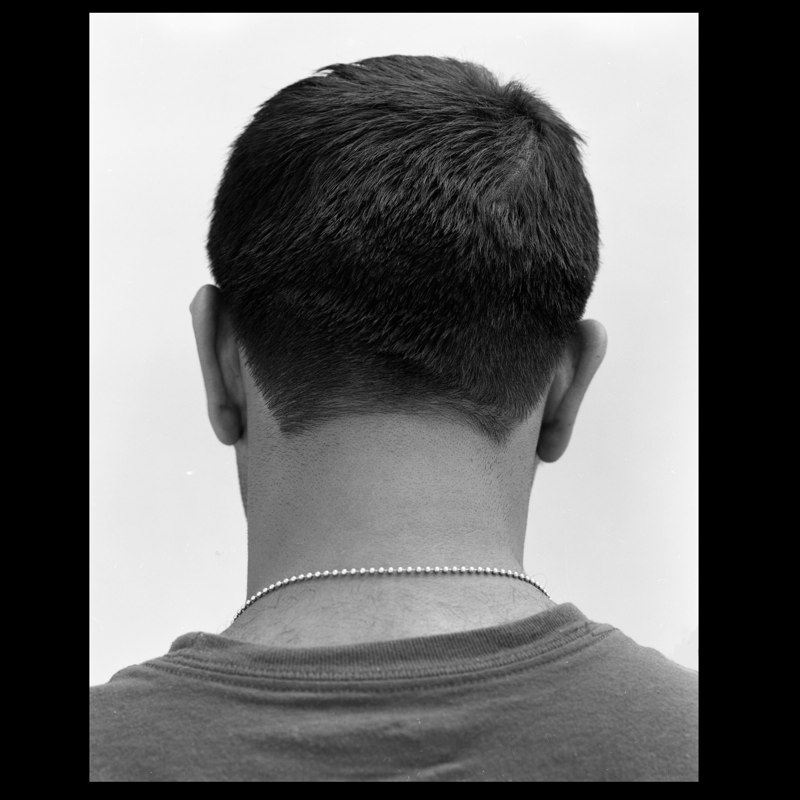

A Pashto linguist who now lives in the U.S. and works with the Marines. He wasn’t allowed to show his face, give his name, or speak to the media, according to his contract with Mission Essential Personnel, a company that provides translators to the U.S. Department of Denfense. Pashto linguists from outside Afghanistan can make more than $200,000 a year, while Pashto linguists from Afghanistan make on average $700 a month.

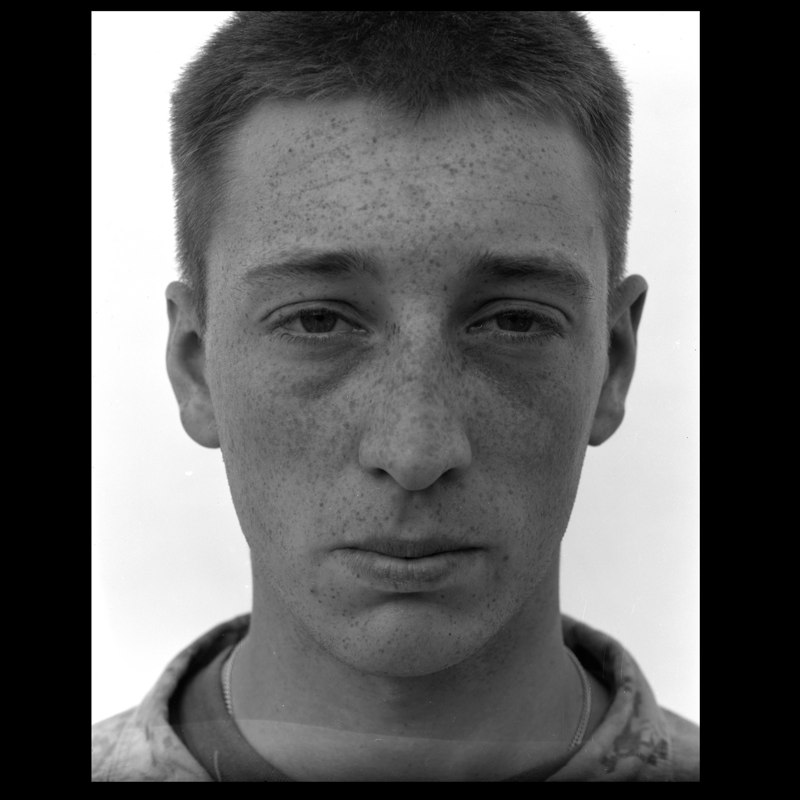

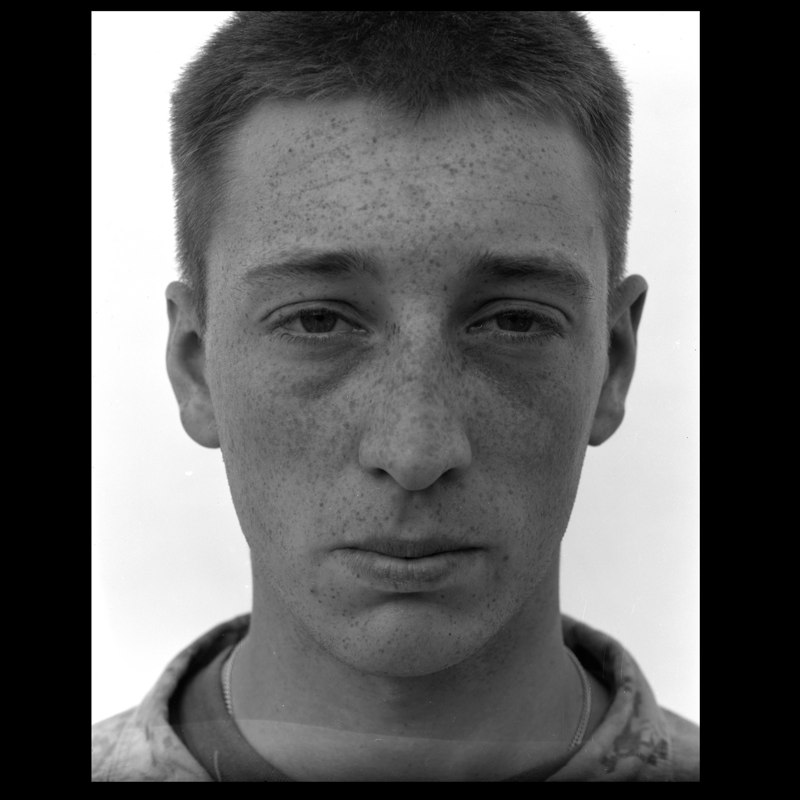

An American Marine in Marja.

An Afghan police officer in Marja.

An Afghan National Army soldier holds a newly adopted puppy with henna on its head and ears at Camp Hill in Marja.

Photographer: Micah Garen